BodyCartography, with a premiere at the Walker this weekend, boldly explores both inner and outer landscapes.

Article by: Kristin Tillotson

Source: Star Tribune

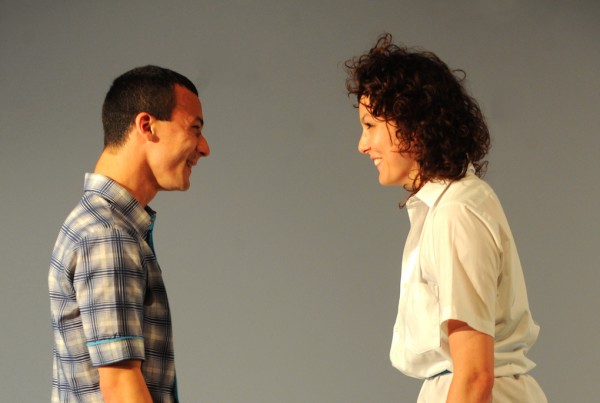

Even while recoiling in distaste, professional dancers exude grace. That’s why Anna Marie Shogren could look so artful as she twisted away when Francesca Mattavelli repeatedly placed a popping, crackling contact mike on various parts of her body.

“We’re calling this part ‘the uninvited massage,'” said Otto Ramstad, who with his wife, choreographer Olive Bieringa, leads BodyCartography Project, a Minneapolis contemporary-dance group. They were rehearsing “Super Nature,” Walker Art Center‘s largest dance commission of the season, set to premiere on its McGuire stage this weekend.

While preview material referencing “animal appetites” and a “radical ecological melodrama” might lead you to believe the work will focus on our baser natures, it’s also very much about empathy, Ramstad said — giving and receiving it, exploring when and why we feel it.

“Dance is an empathy machine,” he said. “It’s really good at projecting that, both between the dancers and between them and their audience. When you watch [Shogren’s] discomfort, you feel it, too.”

The seven dancers include Emily Johnson, who last week won a national Bessie award, and Ramstad. A moving set designed by Ramstad’s twin brother, Emmett, who also did the costumes, promises added drama, complete with hanging ropes, trees and fog machines. A live score will be performed by composer and harpist Zeena Parkins (another Bessie winner), augmented by wind blowing through trees and other natural sounds recorded at Theodore Wirth Park.

Body Cartography was founded by Bieringa in San Francisco in 1997. Ramstad, who grew up in Minnesota, became co-director two years later. Since then they have staged live work and made acclaimed dance films around the world, from Bieringa’s native New Zealand to the U.K. They are particularly known for ambitious site-specific work at locations ranging from remote natural wonders like the Joshua Tree desert to busy Nicollet Avenue in Minneapolis, where Bieringa recently drew curious looks as she rolled along the ground and crouched inside a restaurant’s sidewalk sign.

Working in such “social landscapes” is a special kind of challenge, she said. “You have to be in this deep, embodied physical experience and at the same time be engaged with the people around you.”

She described the new work as being “extremely physical, without relying on traditional dance vocabulary. Say you’re in a supermarket, there are inherent rules you’re supposed to follow, but what happens if you give in to your internal desire, what you feel like doing at that moment, like maybe yelling?”

Walker seeks risky work

It’s that kind of fearless exploration of social mores and artistic boundaries that attracted the attention of Philip Bither, who heads the Walker’s performing-arts division.

“Every commission is a risk, but our focus is on who’s doing groundbreaking work, who’s moving the artistic discipline forward and working in ways we haven’t seen before,” Bither said. “We’d been watching as they grew artistically stronger, more intellectually complex, and the time was right.”

By giving Body Cartography Project such a substantial commission (a combined $40,000 in cash, tech support and studio time), the Walker confers increased status upon the teams as it continues to build an international name. In June, they went to France to perform”Mammal,” a commission from the Lyon Opera Ballet they put together in less than three weeks.

“Super Nature” is informed, in part, by an experiment the dancers conducted at the Walker last spring, a performance installation carried out in an empty museum gallery. Interested participants signed up to interact one on one with a dancer in the darkened space, which grew lighter as the two got closer. Neither dancer nor “audience” had any idea what the other would do, which variously included standing frozen in place, pacing, jumping, running, bouncing off walls, singing and making or avoiding eye contact.

Whether they were trying to or not, they were playing off each other, with sometimes surprising results, said Ramstad: “What I took away from it is that we think our reactions to others are learned, refined, but they’re really more instinctual than we realize.”

Asked how they would coax possible ticket buyers who feel apprehensive about modern dance to come see them at work, Bieringa and Ramstad each had a ready answer.

“Let yourself have an experience you don’t understand,” she said. “Value the unconscious as much as the conscious.”

“Look at watching live performance as not a break from your life, but a part of your life,” he said. “Being in the audience is a social experience, too.”